|

The Urie Houff, the family mausoleum for the Barclays of Urie, was featured in a previous Barclay Blog. Recently, a nice family who lives near the mausoleum contacted us and let us know that they have a lovely view of the Houff from their property. They are unassociated with Clan Barclay or the Urie Houff, but they have a mutual interest in its restoration and conservation. We are sending a very sincere thanks to Bill Wildsmith and MeYoung Choi for sharing your beautiful photos! Enjoy the view and dream of visiting Scotland! Which is your favorite photo? Let us know in the comments below! Click here for more information about the location of the Urie Houff.

1 Comment

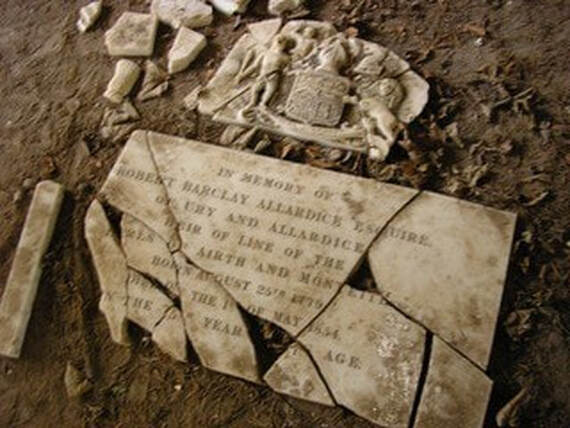

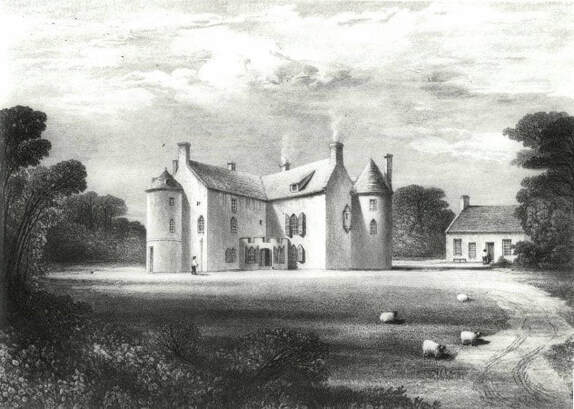

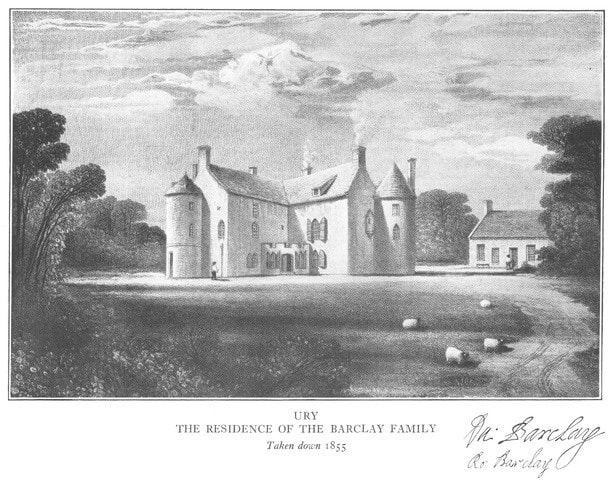

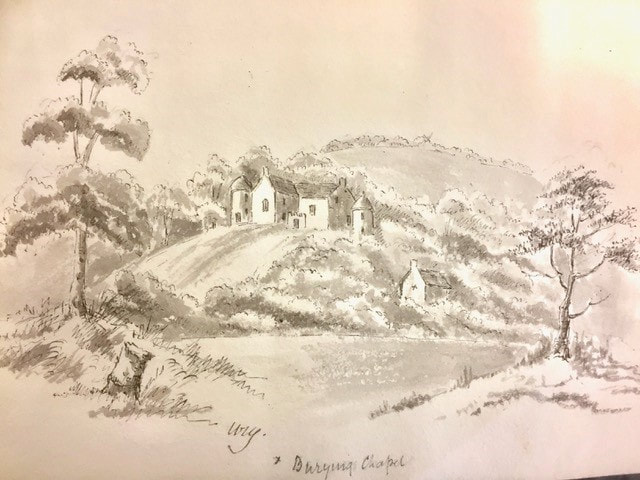

Part I: By Humphrey John Barclay, Chief of the House of Barclay of Mathers and Urie Ury was a Scottish estate of rolling hills and woods, south of Aberdeen, reaching towards the sea at the fishing village of Stonehaven and adjoining the great fortress of Dunnottar Castle (below), once guardian to the Scottish Crown jewels, which to this day towers forbiddingly on its rocky promontory above the shore. Ury House (below) had been built in the 1670s by Colonel Robert Barclay Allardice's great-great-great grandfather, the first Laird Colonel David Barclay, when he acquired the estate on which the previous house was burnt in 1645 by Royalist troops. Somewhat grim, even formidable in appearance, it featured within yards of its front door a Quaker Meeting House added after the Colonel David Barclay's conversion to the faith, which formed a vital element of his life, and that of his son, the celebrated Quaker Apologist Robert Barclay Ury II, and for many generations of the family thereafter. The family was thus brought up in a forbidding, if characterful, turreted Scottish manor house. It was said to be "far from homely" – "a curious old house with hiding places for times of danger," according to Elizabeth Wheeler in 1840. In Ury IV’s time, she adds, "There was no hall door and the only entrance was at the top of the house" so that (according to another source) visitors had to be hoisted up to the third floor in a basket! Elizabeth continues: "His son had a doorway cut out in the usual place, but the walls were so thick and hard that the masons could carry away in their aprons at night all the stuff they had hacked out in in the day." Samuel Galton’s diary written in 1839 confirms this, and records that staircases had "subsequently been cut out of the solid wall." And Arthur Kett Barclay wrote in 1854: "The low battlemented basement entrance, of much later date than the Bairn or fortress itself, is out of character." There was some decoration inside "in Italian fresco style," but its stone walls would have been bare to our eyes, dimly candlelit, and certainly cold except when in front of roaring fires in the great hall and kitchen. Outside however, the huge grounds of the estate offered endless scope for play and adventure. This view (below) is from the north part of the estate, looking towards the sea past the Howff burial ground hidden in the trees. Elizabeth Wheeler recalls that "the farming was splendid, and we walked through a field of wheat which was taller than a man." Ury was a Spartan sportsman’s house, and largely unchanged since the time of the Great Master, Robert Barclay Ury V, father of Captain Robert Barclay Allardice. In tune with the Captain's life, there were sporting pictures all over the Hall, Porch and Dining Room, and no concessions were made to effeminacy or comfort. A visitor wrote: “I do not recollect seeing even an armchair in the house. For those in the dining room, if the seats of them were made of hearts of oak itself they could not be much harder than they are, and the backs of them are as straight, and nearly as high, as a poplar tree. I believe there is a sofa in the drawing-room, but as for ottomans and footstools, and such like, you might as well look for an elephant at Ury.” This was the house where the Pedestrian, Captain Robert Barclay Allardice, and his spinster sister Rodney lived, and where the gloomy Great Hall became the setting of one of the best ghost stories ever… Part II: Found in A History of the Barclay Family, Part III, pp 231-233: Before saying farewell to the old House of Urie one more story remains to be related. The reader may form his own judgement on its authenticity….

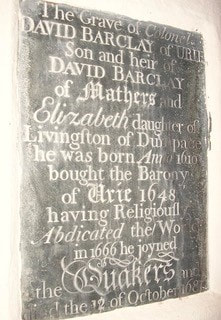

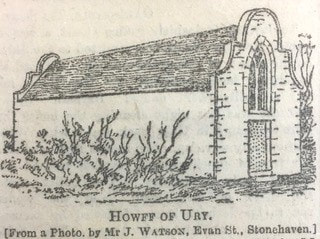

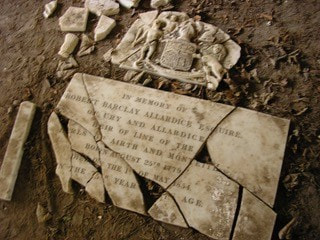

“Lindley Murray Hoag, when he visited Aberdeen, expressed a wish to visit Ury, and Captain [Robert] Barclay [Allardice] hospitably invited him to stop there and sleep on his return journey to the South, adding that by doing so he would see the place both by daylight and by candlelight. It was a raw afternoon in October when Hoag started and by the time the conveyance reached Ury he felt himself thoroughly chilled, and requested to be allowed to go straight to his room and have a basin of gruel in bed. The next morning, at breakfast, they were standing as people do before the fire, when Hoag, looking at an old portrait of the soldier who fought ‘ankle deep in Lutzen’s blood,’ remarked, ‘Ah, there is my friend of last night.’ “’Not quite,’ said Miss [Rodney] Barclay. ‘That is an ancestor of ours who has been dead nearly two hundred years.’ “’Oh,’ said Hoag, ‘he looks like the old gentleman who came into my room last night.’ “At this juncture breakfast was served, and Captain Barclay seemed deep in thought. At last he said, ‘Will you please tell me, Mr. Hoag, who it was that came into your room last night and what was he doing there?’ “’Well,' replied Hoag, ‘I was just going off to sleep when there was a knock at the door and a sweet old gentleman very much like that portrait came into the room, and he apologised for disturbing me. He then went round to the foot of the bed and opened a cupboard in the wall at the other side, taking out some old papers which looked like parchments.’” “’Did ye ever hear the like o’ that!’ exclaimed both the Barclays. ‘Why, there is no cupboard there.’ “Captain Barclay remained thinking, and when breakfast was over he said, ‘Mr. Hoag, will you please do me the favour of showing me exactly where the old gentleman found the papers?’ “They all three went upstairs, and sure enough there was no appearance of any cupboard, but the wall sounded hollow. Barclay tore off the paper and found some wooden boarding. This he broke off with the poker, and an iron door was laid bare. He tried fruitlessly to open this and then sent for a blacksmith, who found and opened a safe door…and in the safe were the missing deeds [the family had urgently been searching for because they were needed for legal matters regarding the estate]. “Miss Barclay ever after used to speak of entertaining angels unawares whenever she related the circumstances of Lindley Murray Hoag’s visit to Ury.” From this incident it would seem that a portrait of Colonel David existed in 1849, but it has never been traced and there is no other record of it. By Leah Parker, MAEd, Barclay Genealogy Researcher In our last blog, we visited the lovely coastal town of Stonehaven, which was heavily influenced by members of Clan Barclay. Just two and a half miles northwest of Stonehaven stands the ruins of the Urie Estate, home to Colonel David Barclay, first laird of Urie, and subsequent lairds of Urie and also headquarters of the Quaker movement in Scotland. (Note that we find spellings Urie and Ury in records, but we will default to the Urie spelling here.) Urie has a rich history, and I want to share some of its stories with you. The Gazetteer for Scotland shares the following history of Urie: "Urie [was] a mansion in Fetteresso parish, Kincardineshire, on the left bank of Cowie Water, 2 miles NNW of Stonehaven. ...The first known possessors of the estate were the Frasers, a family of renown in early Scottish history, whose chief was designated Thane of Cowie. Through the marriage of Margaret Fraser with Sir William Keith, it passed to the Marischal family. The barony of Urie, which then included the lands of Elsick and Muchalls, was sold in 1413, along with other possessions, to William de Hay, Lord of Errol. It remained in the possession of the Hay family till 1640, when the estate of Urie was purchased by William, Earl Marischal, Elsick and Muchalls having in the interval passed into other hands. About 1647 it was sold to Col. David Barclay, third son of Barclay of Mathers, the representative of the ancient De Berkeleys. Col. Barclay, 'having religiously abdicated the world in 1666 and joined the Quakers,' at his death in 1686 was succeeded by his son, Robert Barclay (1648-90), the famous Quaker apologist." A History of the Barclay Family, Part III, unfolds this story: “…Colonel [David] Barclay looked with a discerning eye on the gently undulating ground, the ‘little hills’ from which the shire of the Mearns derived its name, the sunny southern slopes where the young saplings were already beginning spring again, the Cowie River with its fresh and salt water, and excellent salmon and trout fishing. We may conclude from the many references to the rights, that both the Colonel and his son [Robert] were keen fisherman. The easy approach to the seaport of Stonehaven was also of great importance in those days…” (pp 23-24). “We can imagine with what thankfulness of heart David Barclay set to work to build his house and restore his property. He erected a long, low, solidly built mansion out of great blocks of local granite, on the top of a steep bank, at the foot of which ran the burn. It faced south-east, so the morning sun shone on its steep roofs and whitewashed walls. He built it with two ‘pepper-pot’ turrets, a sign of the characteristic of those times, a sign of the occupancy of the owner… (p 75). “As soon as the house was completed [Colonel David Barclay Urie I] handed over the whole property to his son Robert, who had married in 1669.... Urie from henceforth became the centre of the Quakers in the north, and the meetings there held first monthly, and then weekly, were attended by increasing number of tenants and neighbours….” (p 76). Notice the little meeting house to the right of the castle. “David Barclay… made a burial ground on the top of a steep hill in Urie… which he purposed to surround with a stone wall and locked gate, so that no unauthorised person could break in. He left the building of the wall to his son Robert, in his last directions. Here lie the Colonel himself, his son Robert and his wife, with the successive members of this family who inherited Urie, down to the year 1853” (p 77). This mausoleum became known as the Urie Houff. After Robert Barclay Urie III inherited the estate, he set to work improving it, “and a description of the property in 1722 gives a clear picture of his environment. It speaks of the ‘Mannor Place of Urie’ as ‘being charmingly surrounded with very fine gardens, the south wall of which is washed with the water of Cowie, and the East is so near a large brook that nothing intervenes but a slip of ground planted with fir trees, for a fence to the garden. This brook is well stockt with large fine trouts, and runs through an enclosure of cow pasture. It is very healthfully placed upon a gravelly soil, sloping to the south towards the river, so that the gardens are very delightfully placed below one another, quite to the river side, and although standing upon an eminency, which gives it a good prospect of the sea.... The house is an old castle-built house having very thick walls.... [A]lso…to the north west of the house he hath a larger loch in which were found an old helmet with a name supposed to be Danish, and shin pieces, which he gave to Sutherland the antiquary…. The advantage of the Estate House being rightly considered in the healthfulness of its situation, the regularity of its gardens, the extensiveness of its enclosures, the nearness of a seaport town, the plenty of fishing, both in salt and fresh water, the abundance of game of all sorts both at sea and land, makes it a very delightful habitation’” (pp 203-205). “On the death of Captain Robert Barclay-Allardice [Urie VI] in 1854 , the representation for the family passed to Charles Barclay of Bury Hill, great-grandson of David Barclay of Cheapside, second son of the Apologist, who became ‘Chief of Mathers and Urie’” (p 231). The Gazetteer for Scotland picks up the story here: "[Robert Barclay, the Quaker Apologist's] great-grandson and namesake (1751-97) in 1777 married the heiress of Allardice…, and improved the estate, granting feus, from which the New Town of Stonehaven has arisen. His son, Capt. Rt. Barclay-Allardice (1779-1854), was famous as an agriculturist, and still more for his pedestrian feats, having in 1809 walked 1000 miles in 1000 consecutive hours. At his death the estate was purchased by the late Alex. Baird, Esq., ironmaster at Gartsherrie, who was succeeded in 1862 by his brother, John Baird, the father of the present laird, Alex. Baird, Esq. (b. 1849; suc. 1870). With the adjacent estate of Rickarton, purchased in 1875, the lands extend to about 10,000 acres, and yield a rental of about £7500." The Baird family built a new house and completed it in 1885 in the Elizabethan style. It was the largest mansion in the county at the time. The house was damaged by fire and has since fallen into a state of disrepair. And what of the Urie Estate today? If you want to visit Urie, you will have to wait. I know because I tried. I found it on a map but only got as close as the small road that forks off the main road. The small road was closed due to the reconstruction project. I was able to snap a photo of an old round structure with a plaque labeling it “Ury North Lodge” at the beginning of the small road, though. Old Map of Urie and Surrounding Area Current Map of Urie and Surrounding Area Neglected for years, plans are in place to restore the 1885 estate. FM Group is reconstructing the building to house luxury flats and developing an 18-hole Jack Nicklaus Signature Championship Golf Course. I hope to visit this place when it is ready to welcome visitors! Please can I book my flight to Scotland?

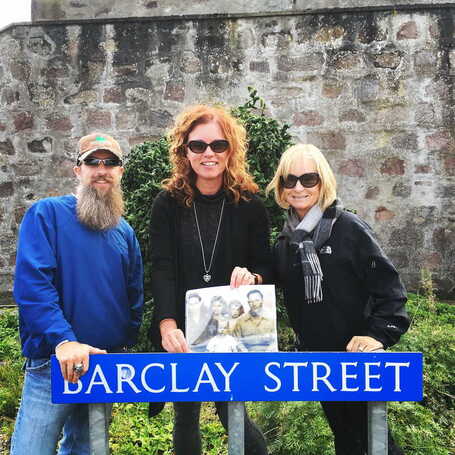

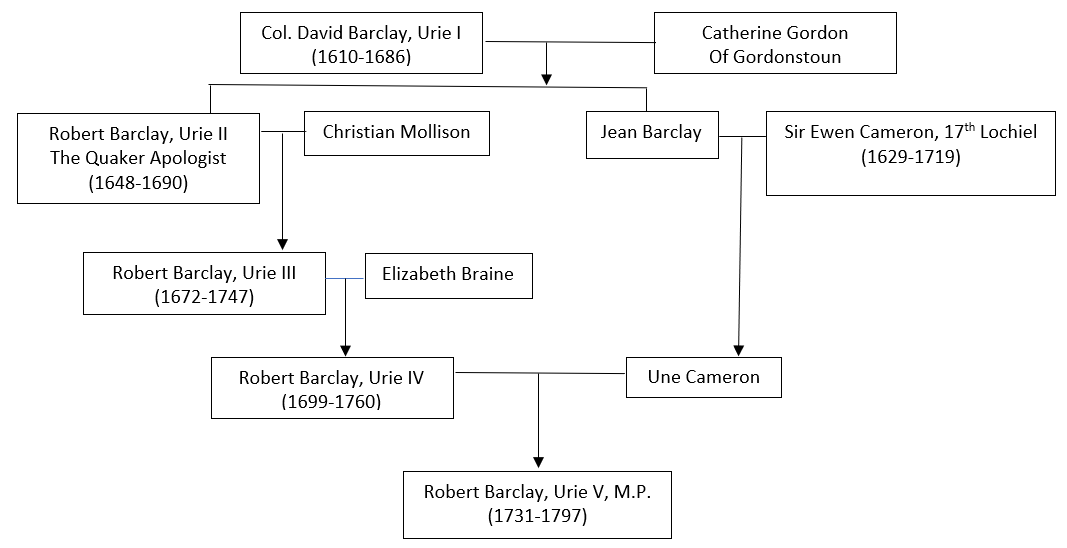

By Leah Parker, MAEd, Barclay Genealogy Researcher In our last blog post, we explored Dunnottar Castle. You may recall that I recommend you visit in the morning to avoid crowds and gusty afternoon winds that sometimes close access to the castle. After visiting Dunnottar, make your way to the nearby town of Stonehaven. There is a lovely trail that follows the coast from the castle to town, and it is easily walkable. I would suggest that you drive over, though, freeing up space in the small car park for the castle. After a morning visit to the castle, it will be the perfect time to get lunch in Stonehaven. The Waterfront Café and Bar on Allardice St. (B979) is a nice place with a lovely view. Then be sure to visit Barclay Street. If you go to the north end of the street, there is a large sign that says “Barclay Street” in front of a stone wall, and it makes for a fun photo opportunity. Now for a little history. Stonehaven is a pretty coastal town south of Aberdeen, heavily influenced by our Barclay kin and their friends and family. History of the Scottish Barclays explains on p 58: “Robert Barclay [Urie V], was born 27th November 1732, and succeeded his father 10th October 1760. He sat as M.P. for Kincardineshire in three successive Parliaments, and was well known in Scotland as a practical agriculturalist. The Laird laid the foundations of the new town of Stonehaven [on the old town of Stonehyve] by feuing certain lands which he had acquired. He died 8th April 1797. He married, first, 3rd June 1753, his cousin Lucy Barclay, only daughter of his uncle David and by her who died 23rd March 1757, he had issue one daughter…. Urie married, secondly, 2nd December 1776, Sarah Ann Allardice.” Their son and heir to Urie was Robert Barclay-Allardice (1779-1854), father of the sport of pedestrianism, precursor to racewalking. But more on him in a later blog… If you examine a map of Stonehaven, you will find street names reflecting the impact of the Barclays of Urie. For example, names of the streets include “Barclay,” “David,” “Robert,” “Urie Cres,” “Allardice,” and “Cameron.” Almost all of those names should be recognizable to anyone familiar with the Barclays of Urie, but what about Cameron? Do you know that name? Let’s look at an abbreviated family tree that highlights the connection. (Note that there are other children and siblings not noted on this tree. The purpose of this tree is to demonstrate the Barclay/Cameron relationship.) A fuller family tree can be found in A History of the Barclay Family, Part III. If you are unfamiliar with Ewen Cameron, let me introduce you. Sir Ewen Cameron of Lochiel (1629-1719) was a Scottish highland chief, the 17th Lochiel. Sir Ewen married three times, and his third wife was Jean Barclay, daughter of Colonel David Barclay, Urie I (1610-1686). Then Ewen Cameron and Jean Barclay’s daughter, Une Cameron, married Robert Barclay, Urie IV (1699-1760). Consider the irony. Although he was the son-in-law of Colonel David Barclay (early Quaker pacifist) and brother-in-law of Robert Barclay (renowned Quaker Apologist), Sir Ewen Cameron of Lochiel followed the tradition of his Cameron forefathers and was an important Scottish warrior chief. There is a well-known story about a particular one-on-one battle in which he engaged with an English soldier. John Drummond in his Memoirs of Sir Ewen Cameron of Locheill gives the following account of that infamous encounter on pp 118-119 (original spelling used here): It was his chance to follow a few that fled into the wood, where he killed two or three with his own hand, non having pursued that way but himself. The officer who commanded the party had likewayes fled thither, but concealing himself in a bush, Locheill had not noticed him. This gentleman, observing that he was alone, started suddenly out of his lurking-place, and attacked him in his return, threatning, as he rushed furiously upon him, to revenge the slaughter of his countreymen by his death. Locheill, who had also his sword in his hand, received him with equall resolution. The combate was long and doubtfull; both fought for their lives; and as they were both animated by the same fury and courage, so they seemed to manage their swords with the same dexterity. The English gentleman had by far the advantage in strength and size, but Locheill exceeding him in nimbleness and agility, in the end tript the sword out of his hand. But he was not allowed to make use of this advantage; for his antagonist flyeing upon him with incredible quickness, they inclosed and wrestled till both fell to the ground in other's arms. In this posture they struggled, and tumbled up and doun till they fixt in the channell of a brooke, betwixt two straite banks, which then, by the drouth of summar, chanced to be dry. Here Locheill was in a most dismall and desperate scituation; for being under most, he was not only crushed under the weight of his antagonist, (who was an exceeding big man,) but likewayes sore hurt, and bruized by many sharp stones that were below him. Their strength was so far spent, that neither of them could stirr a limb; but the English gentle man, by the advantage of being uppermost, at last recovered the use of his right hand. With it he seized a dagger that hung at his belt, and made severall attempts to stab his adversarey, who all the while held him fast ; but the narrowness of the place where they were confyned, and the posture they were in, rendering the execution very difficult, and almost impracticable, while he was so straitly embraced, he made a most violent effort to disingadge himself ; and in that action, raiseing his head and streaching his neck, Locheill, who by this had his hands at liberty, with his left suddently seized him by the right, and with the other by the collar, and jumping at his extended throat, which he used to say, “God putt in his mouth,” he bitt it quitt throw, and keept such hold of his grip, that he brought away his mouthfull! This, he said, was the sweetest bite ever he had in his lifetime! The reader may imagine in what a pickle he would be, after receiving such a gush of warm blood, as naturally flowed from so wide ane orifice. Ummm... Yikes! Did you get that? Ewen Cameron bit through the throat of his English adversary in order to defeat him. One more item of note: When Bonnie Prince Charlie landed in Scotland in August 1745, he was met by Donald Cameron the 19th Lochiel, grandson of Sir Ewen Cameron, and he pledged his clan’s full support to Charles. Some sources contend that the “Jacobite rising of 1745 might never had happened if Lochiel had not come out with his clan.” The men of Clan Cameron were warriors like their fathers before them, fighting as Jacobites at the Battle of Prestonpans, Battle of Falkirk, and on the frontlines at the Battle of Culloden. Donald Cameron survived Culloden and took refuge in France, where he died in 1748.

I visited Culloden in August 2019, and I wandered the grounds with our tour guide and told her about our Barclay connections to Clan Cameron. When we boarded the tour bus after seeing Culloden, she took the speaker to announce to the group: “Among us we have someone with a connection to Clan Cameron who played an important part at Culloden. Let’s congratulate her.” The busload of visitors erupted in applause, and when they figured out it was me, there were plenty of smiles and pats on the back. Not that I did anything special. I just happened to be born into a family with some interesting connections to history. By Leah Parker, MAED, Barclay Genealogy Researcher Dunnottar Castle is another beautiful place in Scotland with ties to Clan Barclay. I find it to be utterly enchanting, and it is one of my favorite castles on the planet. Dunnottar was the seat of Clan Keith and now stands in ruins perched on a cliff on the northeastern coast of Scotland, about 2 miles or 3.2 km south of Stonehaven. The name Dunnottar is Scottish Gaelic: Dùn Fhoithear, meaning "fort on the shelving slope." The buildings we see today are mostly from the 15th and 16th centuries, but the site is believed to have been fortified in the Early Middle Ages. Dunnottar has played a prominent role in the history of Scotland even through the Jacobite risings of the 1700s because of its strategic location and defensive strength. Dunnottar is best known as the place where the Honours of Scotland, the Scottish crown jewels, were hidden from Oliver Cromwell's invading army in the 17th century. The property of Clan Keith from the 14th century, and the seat of the Earl Marischal, Dunnottar declined after the last Earl forfeited his titles by taking part in the Jacobite rebellion of 1715. The castle was saved from ruin in 1925 and is now open to the public. If you are unfamiliar with the title Earl Marischal, this is a good explanation: The title of Earl Marischal was created in the peerage of Scotland for William Keith, the Great Marischal of Scotland. The office of "Marischal of Scotland" (or Marascallus Scotie) had been hereditary, held by the senior member of the Keith family, since Hervey (Herveus) de Keith, who held the office of Marischal under Malcolm IV and William I. The descendant of Herveus, Sir Robert de Keith (d.1332), was confirmed in the office of "Great Marischal of Scotland" by King Robert the Bruce around 1324. Robert de Keith's great-grandson, William, was raised to the peerage as Earl Marischal by James II in about 1458. The peerage died out when George Keith, the 9th earl, forfeited it by joining the Jacobite Rising of 1715. The role of the Marischal was to serve as custodian of the Royal Regalia [Honours] of Scotland, and to protect the king's person when attending parliament. The former duty was fulfilled by the 7th earl during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, who hid them at Dunnottar Castle. The role of regulation of heraldry carried out by the English Earl Marshal is carried out in Scotland by the Lord Lyon King of Arms. Clan Keith and Clan Barclay were friends, neighbors, and kin to each other. Colonel David Barclay purchased the Urie Estate in the late 1660s from the Earl Marischal, Laird of Dunnottar. (The Urie Estate was about 2.5 miles or 4 km from Dunnottar, but more on Urie in a future blog.) The ties of friendship and kinship were so strong that William Keith, the 7th Earl Marischal of Scotland and Laird of Dunnottar Castle, invited Colonel David Barclay (among a small group of trusted friends) to view the Honours of Scotland when they were hidden in a vault in the castle from Cromwell’s invading army. A History of the Barclay Family, Part III tells the story on pages 50-52: A strong personal friendship as well as the tie of kinship had existed for generations between the two families, and in the Fraser Papers two anecdotes are related which show the pleasant and familiar terms they were on. During the interregnum the care and concealment of the Regalia of Scotland had fallen to the Earl Marishal by right of his hereditary office, and the secret of their whereabouts was only divulged to a very few of his most intimate friends. They were called “The Honours of Scotland,” and consisted of the Crown, the Sceptre, and the Sword. In the Fraser letters there is an account of how David Barclay was privileged to see them. “David Barclay, along with several others, accompanied from Fetteroso, the Earl Marshall with his visitor Earls, Seaforth and Sunderland, to see the Regalia (called The Honours of Scotland) which were kept in a Vault in the Tower of Dunottar Castle, cut out of the solid rock, and cased or lined with lead, and also mahogany, in which they were kept on a table covered with fine linen, and hung with tapestry. “ The Governor of the Castle first opened two locks, and the Earl Marischal a third, with a key taken from a bag hung from his neck by a silver tripet, on which the door of the Regalia was opened, and the Earls kneeled on cushions to view it, after which the attendants got leave by sixes to go and do the same, when the door was locked, and a salute fired from the Castle.” When the Committee of Estates was seized at Alyth in 1651 the Earl Marischal was in possession of this important key, which he wore in the bag round his neck, and must have been extremely anxious lest it should fall into the wrong hands. In the confusion consequent upon the arrest and transhipment of so large a number of people, he was able secretly to send the key to his wife, by a trusty messenger. She managed to save the Honours, and only just in time, as the castle was already surrounded, and was taken by Cromwell a few months later. The Countess Marischal arranged with the wife of the Rev. James Grainger, minister of Kinneff, a small parish church within a few miles of the castle, to remove these precious relics. Mrs. Grainger had been obliged to leave her horse in the besieging camp when she was permitted to enter the castle, approach being only possible on foot. On her return she carried the crown, rolled up in some linen, and must have had an anxious moment when the English General in charge of the blockading Army courteously helped her to mount [her horse], and she took the crown in her lap. Her maid followed her on foot, bearing the sword and sceptre concealed in bundles of lint, which Mrs. Grainger pretended were to be spun into thread. They passed safely through the English army, and arrived at Kinneff, when her husband took charge of them, and wrote to the Countess: “I, Mr. James Grainger, minister of Kinneff, grant me to have in my custody the Honours of the kingdom, viz., the Crown, Sceptre and Sword. For the Crown, and Sceptre, I raised the pavement stone just before the pulpit (in the church of Kinneff) in the night tyme, and digged under it ane hole, and layed down the stone just as it was before, and removed the mould that remained, that none would have discerned the stone to have been raised at all, the Sword again at the west end of the church amongst some common seits that stand there. . . . and if it shall please God to call me by death before they be called for, your Ladyship will find them in that place.” Here they remained till the Restoration, safe in their obscure place of concealment, and visited from time to time by the faithful Graingers to renew the cloths in which they were wrapt. One more item of interest: If you watch Dinsey Pixar's animated movie Brave, you may notice some similarities between the film’s castle DunBroch and Dunnottar Castle. According to The Pixar Times, the creative team behind the movie “wanted a castle in the story, but not a Germanic castle that was Cinderella-like, according to story artist Louis Gonzales. The artists working on the story wanted the castle to be ‘earthy,’ grittier than the pristine ones often seen in animated films. They visited the Eilean Donan and Dunnottar Castles.” So be sure to watch Brave after your next visit to Dunnottar and see if you catch the resemblance. This is one of my favorite castles that I have visited in Scotland, and I highly recommend a visit. If you go, I suggest that you arrive in the morning, as it will be less crowded. (We nearly had the whole place to ourselves when we visited at opening time in September 2016.) The small parking lot can be completely filled by noon. Also, sometimes the winds whip up in the afternoon, making the cliffs dangerous and causing the castle to close to visitors. By the way, the Honours of Scotland are now housed in Edinburgh Castle, which is another great castle to visit. As with Dunnottar, to avoid the most crowded part of the day, I recommend arriving in the morning. Be sure to join one of the free tours once you are in the castle, but go see the Honours first, as the line gets longer as the day goes on. |

AuthorMy name is Leah, and I am the daughter of a Barclay. As an historian and genealogy researcher, I am proud of my Barclay roots and want to preserve and share our stories. Join the conversation at Clan Barclay International Facebook Page.

Archives

March 2021

Categories

All

CLAN BARCLAY INTERNATIONAL

Copyright © 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed