The Weird of Towie

By Tim Barclay, Barclay Historian

Among the more legendary aspects of many Scottish family histories are the often-encountered tales concerning an ancestor supposedly connected with the world of magic, witches and spirits, frequently referred to as “the dark arts.” A weird (or curse), supposedly pronounced by Thomas the Rhymer on the males of the Towie branch of the Barclay family in response to their part in an attack on a nunnery in the twelfth century, is said to have been so feared that it factored in the decision by the owners of Towie-Barclay Castle in the late eighteenth century to sell their inheritance.

“Towie Barclay of the Glen

Happy to the maids

But never to the men.”

A simple examination requires some details be amended. Thomas the Rhymer died in 1298; the lands of Towie, on the north bank of the Ythan six kilometres south-southeast of Turriff, were not acquired by the family until around 1320; no Barclay would be referred to as “of Towie” for another fifty years thereafter.[1] Either then the rhyme’s authorship has either been wrongly attributed or the reference to Towie is an anachronism, or both. Most likely, it is of far more recent origin, perhaps composed around 1600 by the poetically inclined George Barclay of Auchroddie, brother of the laird of Towie-Barclay. Regardless, the possibility remains the rhyme otherwise preserves the memory of a real event with some degree of accuracy.

Two fundamental questions exist about when the raid that supposedly inspired the weird occurred, and which ‘nunnery’ was it that suffered this attack? The twelfth century date provided is obviously too early, but the years following the Rhymer’s death provide a useful point at which to begin an investigation. Almost a decade of campaigning for the return of the rightful king of Scots, John Balliol, had occurred before Robert Bruce’s murder of the Red Comyn at Dumfries and subsequent coronation at Scone on 27 March 1306. For many Scots this was little more than a usurpation that, having already made multiple personal submissions to the king of England over the years, was an unwelcome new hazard. However, the risk of betraying the absent Edward I had to be balanced against the more present dangers of resistance to the Bruce in Scotland, meaning most were compelled (regardless of their personal positions) to provide the military services due to their superiors for their holdings. The subsequent events of 1306-7 thus represented one of the most dangerous periods yet in the Wars for Independence, undoubtedly necessitating acts of discretion and insurance far more frequently than those of conflict and resistance.

At least two Barclays, David and Walter, though previously Comyn supporters, are recorded as having joined the Bruce’s side by mid-1306. With the defeat of the Scots at Methven in June and the arrival of Edward II’s army in Aberdeen in August though, neither David, who then held the Murray lands of Avoch on the Black Isle by grant of the English king, nor Walter, whose lands at Kerko and Monycabbock were sought in a formal petition to the king, were forfeited.[2] Evidently, they had soon reaffirmed their previous allegiances, at least to the satisfaction of their immediate superiors. However, immediately following King Edward I’s death in July 1307 the brothers returned to the Bruce’s side and thereafter remained faithful to the king of Scots.

If the foregoing represents a typical story of shifting allegiances seen in many Scots families at the time, certain idiosyncrasies are relevant. David de Berkeley had been granted Avoch by King Edward in c.1305 at the request of his nephew, Hugh, son of Euphemia de Berkeley and William, earl of Ross.[3] David had very probably also accompanied Hugh when he, just fourteen or fifteen years old, had led the Countess Euphemia’s army against the forces of Sir Andrew de Murray of Petty in July 1297.[4] The earl of Ross, imprisoned in England since being captured at the Battle of Dunbar the previous year, was not released until late 1303.[5] Both his loyalty to King Balliol and his oath to King Edward obliged William not only to refuse service to, but also actively take part against, the Bruce in 1306, and it was perhaps only natural when attempting to evade English retribution in the autumn of that year, the Barclays would seek Earl William’s protection. Conversely, the Barclays were very probably employed as emissaries twelve months later in the negotiations between the earl of Ross and the king of Scots for a truce, and David and Walter de Berkeley certainly witnessed the final submissions of Earl William and Hugh MacTaggart to King Robert at Auldearn in October 1308.[6]

The agreements between the king and earl were significant. Obviously, the treaty between them in autumn 1307 allowed the Bruce to focus his forces on the Comyns and their supporters encamped in Buchan. Additionally though, as Earl William was previously both a supporter of King Balliol and the Comyns and had steadfastly refused to betray the oath King Edward had extracted from him in 1303, his change in allegiance was an example to others reluctant to accept the Bruce as king. However, the effect of these submissions was also dependent upon the king of Scots’ reaction: chivalry required his old enemies to be pardoned of all crimes and restored to all their holdings once they had come into his peace, and failure on his behalf to act so would only drive men away. No doubt though, Earl William’s case must have tested the king sorely.

The reasons for King Robert’s conflict and the origin of the weird of Towie are likely one and the same. For as the first phase of the Bruce’s reign ended in the autumn of 1306, word reached Earl William’s court that the king’s wife, Queen Elizabeth, accompanied by his sisters, daughter and the Countess Isobel who had crowned Robert at Scone, had reached the sanctuary at Tain, in Easter Ross. Tain was an ancient religious institution offering refuge and protection to all within its boundaries and violation of these principles was a serious crime against the church. This normally would be deterrent enough for most men, but Earl William, as King Edward’s man, was ready to emulate his royal master’s approach to convention. The earl resolved on an endeavour requiring both speed and skill but not large numbers of participants. What he needed were skilled knights and their men-at-arms willing to take part in a sacrilege. What he had were his Barclay in-laws in need of his protection.

As is well-known, the Bruce feminae were captured by Earl William and his men at Tain and then handed over to the English.[7] Queen Elizabeth was placed under house arrest in Holderness for eight years; her sister-in-law, Christina, and daughter, Marjorie, were sent to convents; Mary Bruce and Isabel of Fife were confined in cages hung from the turrets at Roxburgh and Berwick castles. In the weeks that followed, scores of Bruce’s supporters were also executed in a spectacular display of cruelty and slaughter.[8] But no Barclays were to suffer this fate. Their lands were not forfeited, no penalties were imposed. Their loyalty to the English king had been confirmed in action with their brother-in-law at Tain.

“Towie Barclay of the Glen

Happy to the maids

But never to the men.”

A simple examination requires some details be amended. Thomas the Rhymer died in 1298; the lands of Towie, on the north bank of the Ythan six kilometres south-southeast of Turriff, were not acquired by the family until around 1320; no Barclay would be referred to as “of Towie” for another fifty years thereafter.[1] Either then the rhyme’s authorship has either been wrongly attributed or the reference to Towie is an anachronism, or both. Most likely, it is of far more recent origin, perhaps composed around 1600 by the poetically inclined George Barclay of Auchroddie, brother of the laird of Towie-Barclay. Regardless, the possibility remains the rhyme otherwise preserves the memory of a real event with some degree of accuracy.

Two fundamental questions exist about when the raid that supposedly inspired the weird occurred, and which ‘nunnery’ was it that suffered this attack? The twelfth century date provided is obviously too early, but the years following the Rhymer’s death provide a useful point at which to begin an investigation. Almost a decade of campaigning for the return of the rightful king of Scots, John Balliol, had occurred before Robert Bruce’s murder of the Red Comyn at Dumfries and subsequent coronation at Scone on 27 March 1306. For many Scots this was little more than a usurpation that, having already made multiple personal submissions to the king of England over the years, was an unwelcome new hazard. However, the risk of betraying the absent Edward I had to be balanced against the more present dangers of resistance to the Bruce in Scotland, meaning most were compelled (regardless of their personal positions) to provide the military services due to their superiors for their holdings. The subsequent events of 1306-7 thus represented one of the most dangerous periods yet in the Wars for Independence, undoubtedly necessitating acts of discretion and insurance far more frequently than those of conflict and resistance.

At least two Barclays, David and Walter, though previously Comyn supporters, are recorded as having joined the Bruce’s side by mid-1306. With the defeat of the Scots at Methven in June and the arrival of Edward II’s army in Aberdeen in August though, neither David, who then held the Murray lands of Avoch on the Black Isle by grant of the English king, nor Walter, whose lands at Kerko and Monycabbock were sought in a formal petition to the king, were forfeited.[2] Evidently, they had soon reaffirmed their previous allegiances, at least to the satisfaction of their immediate superiors. However, immediately following King Edward I’s death in July 1307 the brothers returned to the Bruce’s side and thereafter remained faithful to the king of Scots.

If the foregoing represents a typical story of shifting allegiances seen in many Scots families at the time, certain idiosyncrasies are relevant. David de Berkeley had been granted Avoch by King Edward in c.1305 at the request of his nephew, Hugh, son of Euphemia de Berkeley and William, earl of Ross.[3] David had very probably also accompanied Hugh when he, just fourteen or fifteen years old, had led the Countess Euphemia’s army against the forces of Sir Andrew de Murray of Petty in July 1297.[4] The earl of Ross, imprisoned in England since being captured at the Battle of Dunbar the previous year, was not released until late 1303.[5] Both his loyalty to King Balliol and his oath to King Edward obliged William not only to refuse service to, but also actively take part against, the Bruce in 1306, and it was perhaps only natural when attempting to evade English retribution in the autumn of that year, the Barclays would seek Earl William’s protection. Conversely, the Barclays were very probably employed as emissaries twelve months later in the negotiations between the earl of Ross and the king of Scots for a truce, and David and Walter de Berkeley certainly witnessed the final submissions of Earl William and Hugh MacTaggart to King Robert at Auldearn in October 1308.[6]

The agreements between the king and earl were significant. Obviously, the treaty between them in autumn 1307 allowed the Bruce to focus his forces on the Comyns and their supporters encamped in Buchan. Additionally though, as Earl William was previously both a supporter of King Balliol and the Comyns and had steadfastly refused to betray the oath King Edward had extracted from him in 1303, his change in allegiance was an example to others reluctant to accept the Bruce as king. However, the effect of these submissions was also dependent upon the king of Scots’ reaction: chivalry required his old enemies to be pardoned of all crimes and restored to all their holdings once they had come into his peace, and failure on his behalf to act so would only drive men away. No doubt though, Earl William’s case must have tested the king sorely.

The reasons for King Robert’s conflict and the origin of the weird of Towie are likely one and the same. For as the first phase of the Bruce’s reign ended in the autumn of 1306, word reached Earl William’s court that the king’s wife, Queen Elizabeth, accompanied by his sisters, daughter and the Countess Isobel who had crowned Robert at Scone, had reached the sanctuary at Tain, in Easter Ross. Tain was an ancient religious institution offering refuge and protection to all within its boundaries and violation of these principles was a serious crime against the church. This normally would be deterrent enough for most men, but Earl William, as King Edward’s man, was ready to emulate his royal master’s approach to convention. The earl resolved on an endeavour requiring both speed and skill but not large numbers of participants. What he needed were skilled knights and their men-at-arms willing to take part in a sacrilege. What he had were his Barclay in-laws in need of his protection.

As is well-known, the Bruce feminae were captured by Earl William and his men at Tain and then handed over to the English.[7] Queen Elizabeth was placed under house arrest in Holderness for eight years; her sister-in-law, Christina, and daughter, Marjorie, were sent to convents; Mary Bruce and Isabel of Fife were confined in cages hung from the turrets at Roxburgh and Berwick castles. In the weeks that followed, scores of Bruce’s supporters were also executed in a spectacular display of cruelty and slaughter.[8] But no Barclays were to suffer this fate. Their lands were not forfeited, no penalties were imposed. Their loyalty to the English king had been confirmed in action with their brother-in-law at Tain.

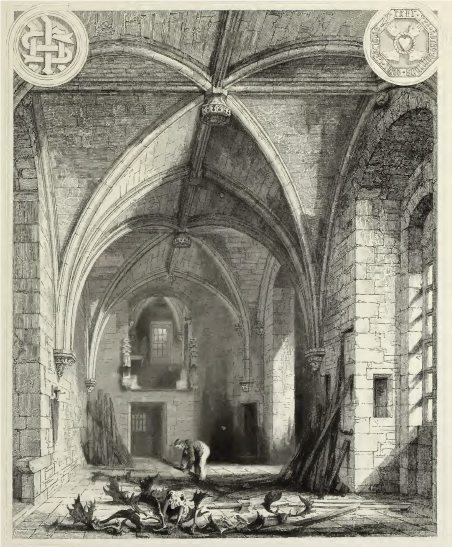

Figure One: Towie Castle interior during demolition works in the nineteenth century. [9]

[1] John Maitland Thomson, ed., Registrum Magni Sigilli Regum Scottorum, I (Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House, 1882), app.2, no.411; Cosmo Innes, ed., Registrum Episcopatus Aberonensis, II (Edinburgh: Spalding Club, 1845), pp.281-2.

[2] Joseph Bain, ed., Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, IV (Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House, 1888), app., no.14; Francis Palgrave, Documents and Records Illustrating the History of Scotland, I (London: Record Commission, 1837), no.CXLII(87).

[3] John P. Ravilious, “The Ancestry of Euphemia, Countess of Ross: Heraldry as Genealogical Evidence,” The Scottish Genealogist, Vol. LV No.1 (March 2008), pp.33-38.

[4] Joseph Bain, ed., Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, II (Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House, 1884), no.922.

[5] Ibid., no. 1399c

[6] The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707, 1308/1 [https://www.rps.ac.uk/trans/1308/1]

[7] Felix Skene, ed., The Book of Pluscarden, II (Edinburgh: William Patterson, 1880), p.177.

[8] Joseph Bain, ed., Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, II (Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House, 1884), no.1811a, b.

[9] Robert William Billings, The Baronial and Ecclesiastical Antiquities of Scotland, IV (Edinburgh: William Blackwood & Sons, 1852), plate 56.

[2] Joseph Bain, ed., Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, IV (Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House, 1888), app., no.14; Francis Palgrave, Documents and Records Illustrating the History of Scotland, I (London: Record Commission, 1837), no.CXLII(87).

[3] John P. Ravilious, “The Ancestry of Euphemia, Countess of Ross: Heraldry as Genealogical Evidence,” The Scottish Genealogist, Vol. LV No.1 (March 2008), pp.33-38.

[4] Joseph Bain, ed., Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, II (Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House, 1884), no.922.

[5] Ibid., no. 1399c

[6] The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707, 1308/1 [https://www.rps.ac.uk/trans/1308/1]

[7] Felix Skene, ed., The Book of Pluscarden, II (Edinburgh: William Patterson, 1880), p.177.

[8] Joseph Bain, ed., Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, II (Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House, 1884), no.1811a, b.

[9] Robert William Billings, The Baronial and Ecclesiastical Antiquities of Scotland, IV (Edinburgh: William Blackwood & Sons, 1852), plate 56.

Clan Barclay International

Copyright © 2021