Feud and Bloodshed

By Tim Barclay, Barclay Historian

To find a dispute over property at the heart of an intra-familial feud is so common in Scottish history as to suggest an almost universal causality of the same. Siblings, cousins, and in-laws squabbled both within and outwith the ecclesiastical and secular court systems, and it was hardly unusual for a settlement in either case to be attempted by armed combat. Evidently, though individuals may not always share the same surname, it was as true in the medieval and post-medieval eras as it is today, that the greatest threat to an individual’s safety comes not from strangers but one’s closest family and friends.

The Scots enjoyed just a few years of peace following the treaty of Northampton of 1328 before King Edward III of England demonstrated his interpretation of his promises of peace towards them and supported the invasion of Edward Balliol. Though Balliol and his ‘disinherited’ supporters were to make multiple attempts they were unable to establish any permanent control, the young King David of Scotland, sent to France as a fugitive in May 1334, did not return until 1341. This left several years in which royal authority was effectively absent from Scotland, providing numerous opportunities in which ambitious individuals could make considerable acquisitions through military action. However, whether they could retain the same depended on whether they had enough resources to protect these assets against the actions of others.

A frequently encountered tale of feud and bloodshed from this period is that of William de Douglas of Liddesdale and Alexander de Ramsay. Douglas was the eldest son of James de Douglas of Lothian, Ramsay the brother of William de Ramsay, later earl of Fife. Douglas led the military campaigns between 1337 and 1342 that freed Liddesdale and Teviotdale in southern Roxburghshire from English occupation and, as a reward for his efforts, he received royal several grants, including Liddesdale and the castle of Hermitage, in royal hands since the forfeiture of William IV de Soules in 1320, and Kilbucho, Newlands and the barony of Dalkeith, recently resigned by John de Graham of Abercorn. Ramsay’s exploits were no less memorable and culminated with his capture of Roxburgh Castle, rebuilt by the English in 1334-5. His success was of course also worthy of recognition but King David II, newly returned from France, had neither the experience nor tact to avoid interfering with the claims of another in such situations. Ramsay was made custodian of Roxburgh Castle and sheriff of Teviotdale, infuriating Douglas, who retaliated by capturing Alexander and imprisoning him in Hermitage Castle, where he died in June 1342.

As a measure of the king’s ineptitude, Douglas’ crime went unpunished and the dead man’s lands were, at the request of the Steward, ultimately granted to his murderer. At best, the royal endorsement of Douglas kept retaliation by Ramsay’s relatives at bay. However, following the king’s capture and imprisonment following the battle of Neville’s Cross in October 1346, the feud was both renewed and enlarged, drawing in the kin and supporters of each family. That the terms kin and supporters were not necessarily synonymous is highlighted by subsequent events.

As is well-known, Liddesdale’s brother, John de Douglas of Dalkeith, married to John de Graham’s sister, Agnes, was killed at Haywood in c.1350 and, in retaliation for his role in the affair, David II de Berkeley, husband of Margaret de Brechin, was then killed in the streets of Aberdeen on 25 January 1351 by John de St Michael, acting on Liddesdale’s orders.[1] Previously, little association has been found between the events of 1342 and 1350-1, but this is due to a lack of understanding, not because they were truly independent. With a wider perspective, the roles of the parties involved is evident as episodes in a much larger, intra-familial feud.

Several factors linking the events in question appear in the records of the Barclay family. For example, the subsequent marriage in 1358 of David II de Berkeley’s younger son, David IV, to Alexander de Ramsay’s niece, Elizabeth, required a dispensation for their being related in the fourth degree.[2] The Ramsays had numerous connections to local families – Margaret de Brechin’s stepmother was Marjory Ramsay; another Marjory Ramsay married David de Wemyss, a close associate of the Barclays of Fife; almost certainly, David I de Berkeley’s marriage was the source of his grandson David IV’s kinship with Elizabeth Ramsay.[3] In 1341 another of David I’s grandsons, John II de Berkeley of Gartly, married Margaret de Graham, now recognised as a close kinswoman of John de Graham of Abercorn, demonstrating another link between the parties in the intra-familial feud.[4] Additionally, by c.1315 David I de Berkeley’s daughter had married John II de Soules of Kirkandrews, younger brother of William IV, the last Soules lord of Liddesdale.[5] John II was killed alongside Edward Bruce at Faughart in Ireland in October 1318 and, less than two years later, William IV was forfeited for his role in the so-called ‘Soules’ conspiracy that also resulted in the execution of his first cousin, David de Brechin, father-in-law of David II de Berkeley.

If the foregoing links are suggestive, one event across these years provides clear guidance. For immediately following the murder of Alexander de Ramsay and, prior to his reconciliation with William de Douglas, King David II granted the custody of Roxburgh Castle to John II de Berkeley.[6] On the one hand, this could simply have been to temporarily place the castle in neutral hands. If so, despite being a relatively obscure northern laird, John’s links to both the Ramsays and Douglases probably made him a suitable choice for this responsibility. However, an entirely different and more convincing factor behind John’s advancement is intimated in a later reference to John as the “kinsman” of Thomas, earl of Mar.[7]

The kinship between John II de Berkeley and Thomas of Mar has eluded previous researchers. Mar’s mother was Isobel Stewart, a consistent supporter of Edward Balliol and the English king throughout her several marriages. Her parents are unidentified but, based on later records concerning Isobel’s children, she was certainly the granddaughter of James Stewart, possibly via his son John who also fell at Faughart in 1318. Interestingly, James’ sister-in-law was Margaret de Bonkle, mother of Margaret de Brechin, wife of David II de Berkeley. However, this only equates to a relationship of affinity between Earl Thomas and John II de Berkeley and could not be the source of their kinship. Notably though, Isobel Stewart wrote several petitions to the English king in the 1330s claiming hereditary rights to the forest of Selkirk and castle of Roxburgh that had pertained “to her ancestors as sheriffs of Teviotdale,” which claims were upheld by inquisition.[8] To whom Isobel was referring is unclear, but most heritable sheriffships (such as can be traced) first appear in the thirteenth century. Our knowledge of those holding the position of sheriff of Teviotdale at this time is far from complete, but Nicholas de Soules of Liddesdale was sheriff in the 1240s and his son, William III, was sheriff in 1289-90.[9] No other family is known to have held the position across multiple generations and William was also keeper of Roxburgh Castle in 1291. Though with the outbreak of war in 1296 no Soules would again be sheriff, it is more than probable it was as a descendant of this family Isobel Stewart successfully claimed her rights in Selkirk and Roxburgh. Presumably, it was for the same reason then others were able to claim the same rights.

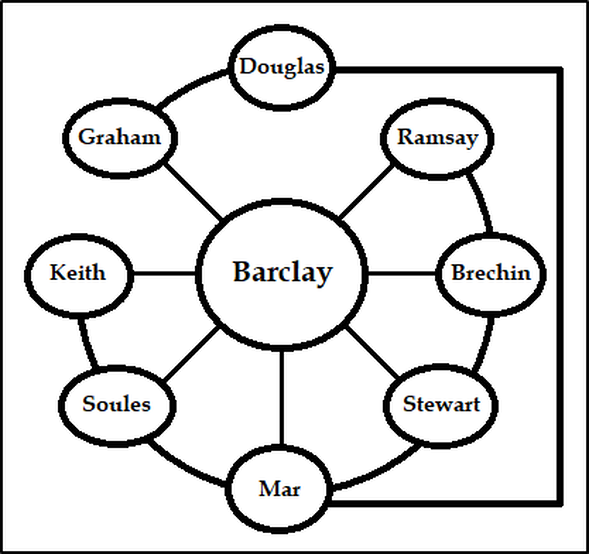

A few pieces of evidence complete the picture (Figure One). William IV de Soules, grandson of the third William and elder brother of John II of Kirkandrews, had two daughters. One of these daughters married John de Keith and became the mother of Robert II de Keith who was recognised by the English administration during his minority in 1335-6 as having hereditary right to half of William II’s lands in Liddesdale.[10] Robert II died sine prole at the battle of Durham in 1346 and, although Isobel Stewart passed away just a few years later, Liddesdale ultimately passed to her son-in-law, William, lord and later earl of Douglas.[11] William possibly married Isobel’s daughter, Margaret, countess of Mar, before David de Berkeley’s death in January 1351 which was soon followed by the marriage of Margaret’s kinsman, Alexander, younger brother of John II de Berkeley, to Katherine de Keith, sister of the Marischal and second cousin to the deceased Robert II de Keith.[12] Notably, John II de Soules’ lands in Kirkandrews and his brother’s lands in Westerkirk (acquired from John de Graham in 1319) were granted to James and Archibald de Douglas (respectively) in the 1320s, and both were then granted to Earl William in early 1354.[13]

The Scots enjoyed just a few years of peace following the treaty of Northampton of 1328 before King Edward III of England demonstrated his interpretation of his promises of peace towards them and supported the invasion of Edward Balliol. Though Balliol and his ‘disinherited’ supporters were to make multiple attempts they were unable to establish any permanent control, the young King David of Scotland, sent to France as a fugitive in May 1334, did not return until 1341. This left several years in which royal authority was effectively absent from Scotland, providing numerous opportunities in which ambitious individuals could make considerable acquisitions through military action. However, whether they could retain the same depended on whether they had enough resources to protect these assets against the actions of others.

A frequently encountered tale of feud and bloodshed from this period is that of William de Douglas of Liddesdale and Alexander de Ramsay. Douglas was the eldest son of James de Douglas of Lothian, Ramsay the brother of William de Ramsay, later earl of Fife. Douglas led the military campaigns between 1337 and 1342 that freed Liddesdale and Teviotdale in southern Roxburghshire from English occupation and, as a reward for his efforts, he received royal several grants, including Liddesdale and the castle of Hermitage, in royal hands since the forfeiture of William IV de Soules in 1320, and Kilbucho, Newlands and the barony of Dalkeith, recently resigned by John de Graham of Abercorn. Ramsay’s exploits were no less memorable and culminated with his capture of Roxburgh Castle, rebuilt by the English in 1334-5. His success was of course also worthy of recognition but King David II, newly returned from France, had neither the experience nor tact to avoid interfering with the claims of another in such situations. Ramsay was made custodian of Roxburgh Castle and sheriff of Teviotdale, infuriating Douglas, who retaliated by capturing Alexander and imprisoning him in Hermitage Castle, where he died in June 1342.

As a measure of the king’s ineptitude, Douglas’ crime went unpunished and the dead man’s lands were, at the request of the Steward, ultimately granted to his murderer. At best, the royal endorsement of Douglas kept retaliation by Ramsay’s relatives at bay. However, following the king’s capture and imprisonment following the battle of Neville’s Cross in October 1346, the feud was both renewed and enlarged, drawing in the kin and supporters of each family. That the terms kin and supporters were not necessarily synonymous is highlighted by subsequent events.

As is well-known, Liddesdale’s brother, John de Douglas of Dalkeith, married to John de Graham’s sister, Agnes, was killed at Haywood in c.1350 and, in retaliation for his role in the affair, David II de Berkeley, husband of Margaret de Brechin, was then killed in the streets of Aberdeen on 25 January 1351 by John de St Michael, acting on Liddesdale’s orders.[1] Previously, little association has been found between the events of 1342 and 1350-1, but this is due to a lack of understanding, not because they were truly independent. With a wider perspective, the roles of the parties involved is evident as episodes in a much larger, intra-familial feud.

Several factors linking the events in question appear in the records of the Barclay family. For example, the subsequent marriage in 1358 of David II de Berkeley’s younger son, David IV, to Alexander de Ramsay’s niece, Elizabeth, required a dispensation for their being related in the fourth degree.[2] The Ramsays had numerous connections to local families – Margaret de Brechin’s stepmother was Marjory Ramsay; another Marjory Ramsay married David de Wemyss, a close associate of the Barclays of Fife; almost certainly, David I de Berkeley’s marriage was the source of his grandson David IV’s kinship with Elizabeth Ramsay.[3] In 1341 another of David I’s grandsons, John II de Berkeley of Gartly, married Margaret de Graham, now recognised as a close kinswoman of John de Graham of Abercorn, demonstrating another link between the parties in the intra-familial feud.[4] Additionally, by c.1315 David I de Berkeley’s daughter had married John II de Soules of Kirkandrews, younger brother of William IV, the last Soules lord of Liddesdale.[5] John II was killed alongside Edward Bruce at Faughart in Ireland in October 1318 and, less than two years later, William IV was forfeited for his role in the so-called ‘Soules’ conspiracy that also resulted in the execution of his first cousin, David de Brechin, father-in-law of David II de Berkeley.

If the foregoing links are suggestive, one event across these years provides clear guidance. For immediately following the murder of Alexander de Ramsay and, prior to his reconciliation with William de Douglas, King David II granted the custody of Roxburgh Castle to John II de Berkeley.[6] On the one hand, this could simply have been to temporarily place the castle in neutral hands. If so, despite being a relatively obscure northern laird, John’s links to both the Ramsays and Douglases probably made him a suitable choice for this responsibility. However, an entirely different and more convincing factor behind John’s advancement is intimated in a later reference to John as the “kinsman” of Thomas, earl of Mar.[7]

The kinship between John II de Berkeley and Thomas of Mar has eluded previous researchers. Mar’s mother was Isobel Stewart, a consistent supporter of Edward Balliol and the English king throughout her several marriages. Her parents are unidentified but, based on later records concerning Isobel’s children, she was certainly the granddaughter of James Stewart, possibly via his son John who also fell at Faughart in 1318. Interestingly, James’ sister-in-law was Margaret de Bonkle, mother of Margaret de Brechin, wife of David II de Berkeley. However, this only equates to a relationship of affinity between Earl Thomas and John II de Berkeley and could not be the source of their kinship. Notably though, Isobel Stewart wrote several petitions to the English king in the 1330s claiming hereditary rights to the forest of Selkirk and castle of Roxburgh that had pertained “to her ancestors as sheriffs of Teviotdale,” which claims were upheld by inquisition.[8] To whom Isobel was referring is unclear, but most heritable sheriffships (such as can be traced) first appear in the thirteenth century. Our knowledge of those holding the position of sheriff of Teviotdale at this time is far from complete, but Nicholas de Soules of Liddesdale was sheriff in the 1240s and his son, William III, was sheriff in 1289-90.[9] No other family is known to have held the position across multiple generations and William was also keeper of Roxburgh Castle in 1291. Though with the outbreak of war in 1296 no Soules would again be sheriff, it is more than probable it was as a descendant of this family Isobel Stewart successfully claimed her rights in Selkirk and Roxburgh. Presumably, it was for the same reason then others were able to claim the same rights.

A few pieces of evidence complete the picture (Figure One). William IV de Soules, grandson of the third William and elder brother of John II of Kirkandrews, had two daughters. One of these daughters married John de Keith and became the mother of Robert II de Keith who was recognised by the English administration during his minority in 1335-6 as having hereditary right to half of William II’s lands in Liddesdale.[10] Robert II died sine prole at the battle of Durham in 1346 and, although Isobel Stewart passed away just a few years later, Liddesdale ultimately passed to her son-in-law, William, lord and later earl of Douglas.[11] William possibly married Isobel’s daughter, Margaret, countess of Mar, before David de Berkeley’s death in January 1351 which was soon followed by the marriage of Margaret’s kinsman, Alexander, younger brother of John II de Berkeley, to Katherine de Keith, sister of the Marischal and second cousin to the deceased Robert II de Keith.[12] Notably, John II de Soules’ lands in Kirkandrews and his brother’s lands in Westerkirk (acquired from John de Graham in 1319) were granted to James and Archibald de Douglas (respectively) in the 1320s, and both were then granted to Earl William in early 1354.[13]

Figure One: Kinship Network of the 14th century Barclays of Fife

As the prior writers would have it, the events of 1342-1351 were put to end when, in August 1353, Lord William de Douglas ordered the assassination of his third cousin and godfather, William de Douglas of Liddesdale. Various reasons have been offered for this and while it is unlikely there was a single cause, the foregoing suggests this was at least partly aimed at finally resolving the larger feud between the heirs and successors of Soules of Liddesdale.

[1] Fordun and Bower, Scotichronicon, Volume II, p.348: Chap. VII.

[2] W. H. Bliss, ed., Calendar of Entries in the Papal Registers, Petitions, Volume I (London: H.M.S.O., 1896), p.331.

[3] Grant G. Simpson and James D. Galbraith, eds., Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland (CDS), V (Edinburgh: Scottish Record Office, 1970), no.614(b); Cosmo Innes, ed., The Acts of the Parliaments of Scotland, I (Edinburgh: 1844), pp.474-5; William Fraser, ed., Memorials of the Family of Wemyss of Wemyss, II (Edinburgh, 1888), no.161; Joseph Bain, ed., CDS, II (Edinburgh: H.M General Register House, 1884), no.1538a.

[4] W. H. Bliss, ed., Calendar of Entries in the Papal Registers, Letters, Volume II (London: H.M.S.O., 1895), p.553.

[5] Joseph Bain, ed., CDS, III (Edinburgh: H.M General Register House, 1887), no.1144.

[6] F. J. Amours, ed., The Original Chronicle of Andrew of Wyntoun, Volume VI (Edinburgh and London: Scottish Text Society, 1908), pp.166-7.

[7] Joseph Robertson, ed., Collections on the Shires of Aberdeen and Banff (Aberdeen: Spalding Club, 1843), p.618.

[8] Joseph Robertson, ed., Topography and Antiquities of the Shires of Aberdeen and Banff, Volume IV (Aberdeen: Spalding Club, 1862), pp.153-4.

[9] Liber S. Marie de Calchou, I (Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club, 1846), no. 157; Joseph Bain, ed., CDS, I (Edinburgh: H.M General Register House, 1881), no. 1699; William Fraser, The Douglas Book, III (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1885), no. 285; Keith J Stringer, ed., Regesta Regum Scottorum (RRS), III (forthcoming), no.325; Joseph Stevenson, Documents Illustrative of the History of Scotland, I (Edinburgh: H. M. General Register House, 1870), nos.68, 89; cf. also David Macpherson, John Caley and William Illingsworth, eds., Rotuli Scotiae in Turri Londinensi, I (London: Record Commission, 1814), p.1a.

[10] CDS, III, p.320.

[11] John Maitland Thomson, ed., Registrum Magni Sigilli Regum Scotorum (RMS), I (Edinburgh: H. M. General Register House, 1882), app.1, no.123.

[12] Bruce Webster, ed., RRS, VI (Edinburgh: University Press, 1982), nos.134-5.

[13] A. A. M. Duncan, ed., RRS, V (Edinburgh: University Press, 1988), no.160; RMS, I, app.1, nos.38, 123.

[2] W. H. Bliss, ed., Calendar of Entries in the Papal Registers, Petitions, Volume I (London: H.M.S.O., 1896), p.331.

[3] Grant G. Simpson and James D. Galbraith, eds., Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland (CDS), V (Edinburgh: Scottish Record Office, 1970), no.614(b); Cosmo Innes, ed., The Acts of the Parliaments of Scotland, I (Edinburgh: 1844), pp.474-5; William Fraser, ed., Memorials of the Family of Wemyss of Wemyss, II (Edinburgh, 1888), no.161; Joseph Bain, ed., CDS, II (Edinburgh: H.M General Register House, 1884), no.1538a.

[4] W. H. Bliss, ed., Calendar of Entries in the Papal Registers, Letters, Volume II (London: H.M.S.O., 1895), p.553.

[5] Joseph Bain, ed., CDS, III (Edinburgh: H.M General Register House, 1887), no.1144.

[6] F. J. Amours, ed., The Original Chronicle of Andrew of Wyntoun, Volume VI (Edinburgh and London: Scottish Text Society, 1908), pp.166-7.

[7] Joseph Robertson, ed., Collections on the Shires of Aberdeen and Banff (Aberdeen: Spalding Club, 1843), p.618.

[8] Joseph Robertson, ed., Topography and Antiquities of the Shires of Aberdeen and Banff, Volume IV (Aberdeen: Spalding Club, 1862), pp.153-4.

[9] Liber S. Marie de Calchou, I (Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club, 1846), no. 157; Joseph Bain, ed., CDS, I (Edinburgh: H.M General Register House, 1881), no. 1699; William Fraser, The Douglas Book, III (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1885), no. 285; Keith J Stringer, ed., Regesta Regum Scottorum (RRS), III (forthcoming), no.325; Joseph Stevenson, Documents Illustrative of the History of Scotland, I (Edinburgh: H. M. General Register House, 1870), nos.68, 89; cf. also David Macpherson, John Caley and William Illingsworth, eds., Rotuli Scotiae in Turri Londinensi, I (London: Record Commission, 1814), p.1a.

[10] CDS, III, p.320.

[11] John Maitland Thomson, ed., Registrum Magni Sigilli Regum Scotorum (RMS), I (Edinburgh: H. M. General Register House, 1882), app.1, no.123.

[12] Bruce Webster, ed., RRS, VI (Edinburgh: University Press, 1982), nos.134-5.

[13] A. A. M. Duncan, ed., RRS, V (Edinburgh: University Press, 1988), no.160; RMS, I, app.1, nos.38, 123.

Clan Barclay International

Copyright © 2021