|

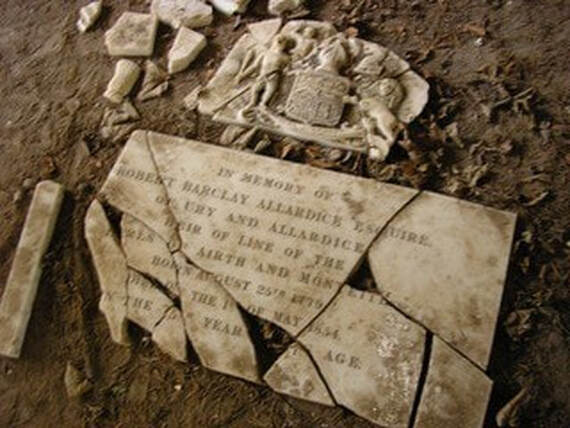

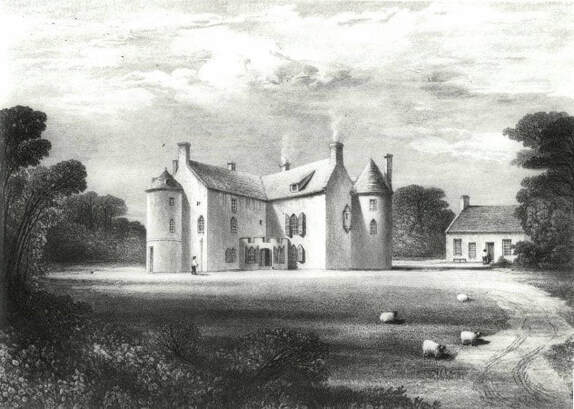

Part I: By Humphrey John Barclay, Chief of the House of Barclay of Mathers and Urie Ury was a Scottish estate of rolling hills and woods, south of Aberdeen, reaching towards the sea at the fishing village of Stonehaven and adjoining the great fortress of Dunnottar Castle (below), once guardian to the Scottish Crown jewels, which to this day towers forbiddingly on its rocky promontory above the shore. Ury House (below) had been built in the 1670s by Colonel Robert Barclay Allardice's great-great-great grandfather, the first Laird Colonel David Barclay, when he acquired the estate on which the previous house was burnt in 1645 by Royalist troops. Somewhat grim, even formidable in appearance, it featured within yards of its front door a Quaker Meeting House added after the Colonel David Barclay's conversion to the faith, which formed a vital element of his life, and that of his son, the celebrated Quaker Apologist Robert Barclay Ury II, and for many generations of the family thereafter. The family was thus brought up in a forbidding, if characterful, turreted Scottish manor house. It was said to be "far from homely" – "a curious old house with hiding places for times of danger," according to Elizabeth Wheeler in 1840. In Ury IV’s time, she adds, "There was no hall door and the only entrance was at the top of the house" so that (according to another source) visitors had to be hoisted up to the third floor in a basket! Elizabeth continues: "His son had a doorway cut out in the usual place, but the walls were so thick and hard that the masons could carry away in their aprons at night all the stuff they had hacked out in in the day." Samuel Galton’s diary written in 1839 confirms this, and records that staircases had "subsequently been cut out of the solid wall." And Arthur Kett Barclay wrote in 1854: "The low battlemented basement entrance, of much later date than the Bairn or fortress itself, is out of character." There was some decoration inside "in Italian fresco style," but its stone walls would have been bare to our eyes, dimly candlelit, and certainly cold except when in front of roaring fires in the great hall and kitchen. Outside however, the huge grounds of the estate offered endless scope for play and adventure. This view (below) is from the north part of the estate, looking towards the sea past the Howff burial ground hidden in the trees. Elizabeth Wheeler recalls that "the farming was splendid, and we walked through a field of wheat which was taller than a man." Ury was a Spartan sportsman’s house, and largely unchanged since the time of the Great Master, Robert Barclay Ury V, father of Captain Robert Barclay Allardice. In tune with the Captain's life, there were sporting pictures all over the Hall, Porch and Dining Room, and no concessions were made to effeminacy or comfort. A visitor wrote: “I do not recollect seeing even an armchair in the house. For those in the dining room, if the seats of them were made of hearts of oak itself they could not be much harder than they are, and the backs of them are as straight, and nearly as high, as a poplar tree. I believe there is a sofa in the drawing-room, but as for ottomans and footstools, and such like, you might as well look for an elephant at Ury.” This was the house where the Pedestrian, Captain Robert Barclay Allardice, and his spinster sister Rodney lived, and where the gloomy Great Hall became the setting of one of the best ghost stories ever… Part II: Found in A History of the Barclay Family, Part III, pp 231-233: Before saying farewell to the old House of Urie one more story remains to be related. The reader may form his own judgement on its authenticity….

“Lindley Murray Hoag, when he visited Aberdeen, expressed a wish to visit Ury, and Captain [Robert] Barclay [Allardice] hospitably invited him to stop there and sleep on his return journey to the South, adding that by doing so he would see the place both by daylight and by candlelight. It was a raw afternoon in October when Hoag started and by the time the conveyance reached Ury he felt himself thoroughly chilled, and requested to be allowed to go straight to his room and have a basin of gruel in bed. The next morning, at breakfast, they were standing as people do before the fire, when Hoag, looking at an old portrait of the soldier who fought ‘ankle deep in Lutzen’s blood,’ remarked, ‘Ah, there is my friend of last night.’ “’Not quite,’ said Miss [Rodney] Barclay. ‘That is an ancestor of ours who has been dead nearly two hundred years.’ “’Oh,’ said Hoag, ‘he looks like the old gentleman who came into my room last night.’ “At this juncture breakfast was served, and Captain Barclay seemed deep in thought. At last he said, ‘Will you please tell me, Mr. Hoag, who it was that came into your room last night and what was he doing there?’ “’Well,' replied Hoag, ‘I was just going off to sleep when there was a knock at the door and a sweet old gentleman very much like that portrait came into the room, and he apologised for disturbing me. He then went round to the foot of the bed and opened a cupboard in the wall at the other side, taking out some old papers which looked like parchments.’” “’Did ye ever hear the like o’ that!’ exclaimed both the Barclays. ‘Why, there is no cupboard there.’ “Captain Barclay remained thinking, and when breakfast was over he said, ‘Mr. Hoag, will you please do me the favour of showing me exactly where the old gentleman found the papers?’ “They all three went upstairs, and sure enough there was no appearance of any cupboard, but the wall sounded hollow. Barclay tore off the paper and found some wooden boarding. This he broke off with the poker, and an iron door was laid bare. He tried fruitlessly to open this and then sent for a blacksmith, who found and opened a safe door…and in the safe were the missing deeds [the family had urgently been searching for because they were needed for legal matters regarding the estate]. “Miss Barclay ever after used to speak of entertaining angels unawares whenever she related the circumstances of Lindley Murray Hoag’s visit to Ury.” From this incident it would seem that a portrait of Colonel David existed in 1849, but it has never been traced and there is no other record of it.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMy name is Leah, and I am the daughter of a Barclay. As an historian and genealogy researcher, I am proud of my Barclay roots and want to preserve and share our stories. Join the conversation at Clan Barclay International Facebook Page.

Archives

March 2021

Categories

All

CLAN BARCLAY INTERNATIONAL

Copyright © 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed