The Earliest Lairds of Gartly

By Tim Barclay, Barclay Historian

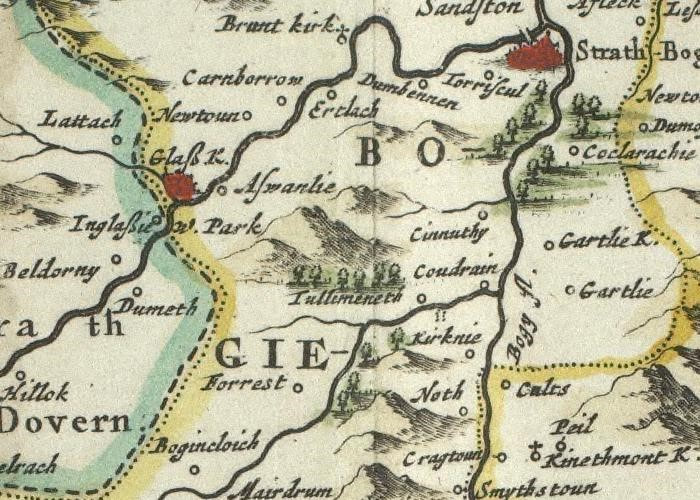

The lairdship of Gartly occupied the eastern half of the parish of the same name in Strathbogie, seven kilometres south of Huntly. In the mid-twelfth century Gartly was part of the Earl of Fife's lands in Strathbogie, but it then passed to William de Murray of Boharm, younger brother of Hugh Freskin de Murray, lord of Duffus and Sutherland, who married Amabel MacDuff, daughter of Earl Duncan II of Fife, around 1190. Around 1210 William granted the “forestam de Garnetulach” (forest of Gartly) to Amabel’s cousin, Simon, son of Waldin de Denmuir, and Sir Simon de Gartly then appears in the records of Aberdeenshire until the late 1250s.[1]

Several clergymen appear from the 1250s occupying the parsonage and prebend of Gartly, which was then in dispute between the bishops of Moray and St Andrews. Master Andrew of Gartly was a canon of Moray in the late 1250s and then a clerk of King Alexander III by the early 1270s, when he was presented with the church of Fordyce (Banffshire) during a vacancy of the see of Aberdeen.[2] Meanwhile, at some point between c.1260 and the mid-1290s, the secular lands in Gartly were acquired by Roger de Mowat, elder son and heir of William II de Mowat, heritable sheriff of Cromarty. Around 1290 Roger granted the Aberdeenshire lands of Gartly, Easter Fowlis and Pitprone to his younger son, Bernard.[3] These gifts were soon confirmed to Bernard by his elder brother, William III de Mowat, but Bernard was taken prisoner at the Battle of Methven and executed at Newcastle in August 1306.[4]

From their bases in Perthshire and further north, the Mowats had spent generations as allies of the Comyns and, following his brother’s death, William III de Mowat remained an opponent of the Bruce until at least 1312.[5] Though King Robert was lenient in his application of the final deadline for recalcitrant Scots to make their submissions, evidently William was too late in coming to the king’s peace. In December 1315, Hugh MacTaggart, son of William, earl of Ross and Euphemia de Berkeley, now married to the king’s sister, Maud de Bruce, received a royal grant of the sheriffdom and burgh of Cromarty and annual rent due from Mowat for the same.[6] Notably, this grant included a promise of warrandice, presumably against Mowat’s claims, meaning the king himself was now personally and legally invested in the dispute. After several more years of protracted dispute, in 1321, disgusted at his treatment and inability to recover his inheritance, William III de Mowat finally quit Scotland for England.

Several clergymen appear from the 1250s occupying the parsonage and prebend of Gartly, which was then in dispute between the bishops of Moray and St Andrews. Master Andrew of Gartly was a canon of Moray in the late 1250s and then a clerk of King Alexander III by the early 1270s, when he was presented with the church of Fordyce (Banffshire) during a vacancy of the see of Aberdeen.[2] Meanwhile, at some point between c.1260 and the mid-1290s, the secular lands in Gartly were acquired by Roger de Mowat, elder son and heir of William II de Mowat, heritable sheriff of Cromarty. Around 1290 Roger granted the Aberdeenshire lands of Gartly, Easter Fowlis and Pitprone to his younger son, Bernard.[3] These gifts were soon confirmed to Bernard by his elder brother, William III de Mowat, but Bernard was taken prisoner at the Battle of Methven and executed at Newcastle in August 1306.[4]

From their bases in Perthshire and further north, the Mowats had spent generations as allies of the Comyns and, following his brother’s death, William III de Mowat remained an opponent of the Bruce until at least 1312.[5] Though King Robert was lenient in his application of the final deadline for recalcitrant Scots to make their submissions, evidently William was too late in coming to the king’s peace. In December 1315, Hugh MacTaggart, son of William, earl of Ross and Euphemia de Berkeley, now married to the king’s sister, Maud de Bruce, received a royal grant of the sheriffdom and burgh of Cromarty and annual rent due from Mowat for the same.[6] Notably, this grant included a promise of warrandice, presumably against Mowat’s claims, meaning the king himself was now personally and legally invested in the dispute. After several more years of protracted dispute, in 1321, disgusted at his treatment and inability to recover his inheritance, William III de Mowat finally quit Scotland for England.

[1] James Balfour Paul, ed., Registrum Magni Sigilli Regum Scottorum, II (Edinburgh: H. M. General Register House, 1882), no.590.

[2] Cosmo Innes, ed., Registrum Episcopatus Moraviensis (Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club, 1837), no.122; Cynthia J. Neville & Grant G. Simpson, eds., Regesta Regum Scottorum, IV (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013), no.167.

[3] National Records of Scotland, RH 1/2/81.

[4] Joseph Bain, ed., Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, II (Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House, 1884), no.1811a.

[5] Joseph Bain, ed., Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, III (Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House, 1887), pp.429-30.

[6] Archibald A. M. Duncan, ed., Regesta Regum Scottorum, V (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1988), no.86.

[7] Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

[2] Cosmo Innes, ed., Registrum Episcopatus Moraviensis (Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club, 1837), no.122; Cynthia J. Neville & Grant G. Simpson, eds., Regesta Regum Scottorum, IV (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013), no.167.

[3] National Records of Scotland, RH 1/2/81.

[4] Joseph Bain, ed., Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, II (Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House, 1884), no.1811a.

[5] Joseph Bain, ed., Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, III (Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House, 1887), pp.429-30.

[6] Archibald A. M. Duncan, ed., Regesta Regum Scottorum, V (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1988), no.86.

[7] Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Clan Barclay International

Copyright © 2021